Blue Gold: The Fight to Stop the Corporate Theft of the World’s Water

By Maude Barlow(excerpt of speech)

From Carnegie Council

What we know from reports by the United Nations, the World Bank, and the World Watch Institute over the last ten years is that we are running out of fresh water in the world because we are diverting, polluting, and depleting the existing sources so quickly that we’re now using up groundwater. Groundwater are the sources of water in aquifers or running rivers underneath the ground. Up until about fifty years ago, very little of that groundwater was used. People had wells, but that took very little water. But now we’re able to put huge bores into these great big aquifers and take huge amounts of water up at a time.

And so what we have is cities, like Mexico City, Bangkok, Beijing, which are literally sinking in on themselves. The weight of the city, giving in on the ground where the water is being removed, causes the whole city to sink. This is called subsidence.

About a quarter of all our water use now around the world is coming from groundwater sources, and that’s only in the last thirty-to-fifty years. So, suddenly, we went from having lots of fresh water on the surface to polluting, depleting, diverting that fresh water, to using the water under the ground at a rate far faster than it can be replenished.

One example is the Ogalala Water Aquifer that goes from the Dakotas down under California. There are 200,000 wells taking water up in that aquifer. The water is being used to grow water-intensive crops like alfalfa and cotton in the desert, which we shouldn’t be doing ecologically. The Ogalala Aquifer is being depleted at fourteen times faster every year than it can be replenished.

Mining or careless use also allow sea water to invade an aquifer and destroy it very quickly. Or if it’s bombed, as in Serbia, a huge water table was infected and destroyed by bombs containing dangerous chemicals. Or it can be a mining tailing that allows poisons and toxic waste to come in, from mining into an aquifer, and it doesn’t take much to destroy a whole table.

The institutions looking at this all agree that the earth’s fresh water is depleting so fast that by the year 2025, fully two-thirds of the world’s population will be living with some amount of stress around water. One-third of the world’s population will have absolutely no access at all.

We already know that twenty-two African countries are running out of water. In South Africa alone, women have to go so much farther now to get water, which is becoming polluted and depleted, that they walk an average of to the moon and back sixteen times every day just to find water for their families. They’re using up the water supply at four times faster than it can be replenished.

We’re now talking about the earth’s “hot stains,” areas where water reserves are absolutely disappearing. It includes the Middle East and northern China. They have diverted water from communities and farms and subsistence farming to their industries because they have been able to actually quantify how much more money they can make on a drop of water if they make a shower curtain liner or running shoe than if they allow it to continue to grow food for the local people. And so there has been massive diversion and fully two-thirds of all of the cities in northern China are now in a water crisis. They’re talking about moving the capital of China from Beijing because Beijing is absolutely running out of water.

In Mexico, they’re talking about moving Mexico City and I don’t know where you’d move 28 million people in the next decade. The Mexican valley is out of water.

California will be out of water in twenty years. Florida is in terrible trouble. The Great Lakes are quite shallow, and we are depleting them so quickly that there is concern by many environmental groups that it may be that one day the St. Lawrence River will no longer reach the ocean. And we’re not talking hundreds of years, but ten-to-fifteen. It has already happened to the Colorado River, the Yellow River in China, and the Ganges in India. Many of the great rivers of the world no longer reach the ocean, and that has huge environmental impacts.

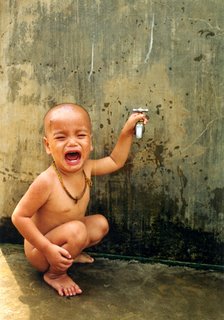

Every eight seconds a child dies in our world from lack of fresh water. But we’re talking about this increasing to the point where it will be as potentially catastrophic as global warming, and perhaps hit us much faster.

I’ve traveled a lot in countries where there isn’t water now, and the catastrophe is not in the future, it’s in the present. It’s probably the most pressing environmental, and therefore political, issue of our day.

Now I would like to address the issue of who owns this water and what do we start to do about it; and how we start to move around this.

We know how to save the world’s fresh water resources. We know we need massive changes in industry. We need laws. Martin Luther King used to say that legislation may not change the heart but it can restrain the heartless, meaning laws around the abuse and pollution of water. We need to stop toxic dumping into our lakes and river systems. We need to stop the destruction of our wetlands and our forests. We need to replace flood irrigation with drip irrigation. We need massive infrastructure repair in our cities, particularly in the developing world, where sometimes as much as 90 percent of all the water is wasted through leaking pipes. We need to use every drop twice as well as we use it now.

We need a new water ethic. We have to start seeing ourselves as animals, like other species, who must respect the laws of Nature and not remain somehow above the laws of Nature, which we currently do.

Unfortunately for all of us, this has come at a time when most governments around the world have bought into the so-called Washington Consensus, which is that there’s only one model of government around the world, and it’s that competitive nation states have to abandon regulatory regimes and allow the market to make decisions around natural resources, health care and education. We are living in a time when absolutely everything is for sale; there’s nothing really sacred anymore from the marketplace. So the fish before they’re caught, the rain before it falls, the seed deep in the forest, our very life itself, everything is up for sale now.

We know that the United Nations and the World Bank had a very important conference two years ago that deemed that water is a human need and not a human right, although an arm of the UN just two weeks ago said no, it’s a human right. This is a very important dispute because you can’t trade or sell a human right, but you can make money on a human need.

Now we have a handful of transnational corporations, backed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, going into developing countries and saying, “as part of your structural adjustment, we want you to convert your public water systems to a private system and we’ll tell you which corporation will come in.”

Some of these companies are startlingly open. They say that the decline of fresh water around the world is a unique and wonderful venture opportunity and will make a huge amount of money. Fortune 500 last year had a special issue on water, saying it is the hottest property out there, invest in water, because people will sell anything for fresh water. You can live for a little while without food, and you can live certainly on basic food, but you cannot live without fresh water.

The annual profits of the water industry now amount to about 40 percent of the oil sector and already substantially higher than the pharmaceutical sector. But we figure that only between 5 and 10 percent of the world’s fresh water has been privatized. So you can imagine the amount of money we’re talking about if it could all be cartelized the way oil has been.

Guy Maddin

By Jason Woloski

From Sences of Cinema

Over the course of a career that has spanned nearly two decades and 25 films, both short and feature, filmmaker Guy Maddin has provided his viewers with more than their fair share of unique, cinematic moments.

To provide just one example, in Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1988), his first feature film, the audience is allowed to watch as one of the director's many eccentric characters, a male who is attempting to make himself more attractive to the ladies relaxing on a nearby beach, disappears behind a dilapidated building, troubled that his hair is dry and in such a mess. At this point, the audience may expect that some grooming is in order, but most first time viewers could never predict how such a grooming process will eventually unfold. Out of sight from the women, the character manages to find a shiny, dead fish, which he then squeezes frantically over his head, until its guts are wretched open, spilling fish oil all over the man's hair. The character soon reemerges, hair slicked back and full of fish oil. He is now ready to properly swoon the ladies still lying on the sands of Gimli beach.

Keeping such a distinct image of a fish in mind, it may be appropriate to consider the career of Maddin in relation to the old cliché about the size of a fish as being relative to the size of the pond that it lives in. In the pond of the Manitoba film industry, he is easily the biggest fish there is. Since making his first short in 1986, titled The Dead Father, Maddin's reputation has, for the most part, only continued to grow with each subsequent project. The fact that he has remained a resident of his hometown, the provincial capital of Winnipeg, throughout his entire life, has only added to his recognition as a Manitoba filmmaker.

Within the pond that is the Canadian film industry, Maddin as fish becomes a bit smaller, having to make room for bigger fish that arrived before him, such as David Cronenberg as well as filmmakers that emerged on the scene at around the same time as Maddin, but have perhaps managed to achieve more far reaching success, at least in their attempts to capture both an international audience, as well as international, critical recognition. Atom Egoyan would be the most obvious example of a successful contemporary director who lives and works in Canada, but whose recognition extends well beyond Canada's borders.

That said, Maddin's exposure has grown considerably in the past few years. In 2000, as part of the Toronto Film Festival's twentieth anniversary celebration, 20 Canadian filmmakers, including Maddin, Cronenberg, and Egoyan, were each commissioned to make a short film. The resulting twenty shorts randomly played before feature films throughout the entire festival. By the festival's conclusion, Maddin's short, titled The Heart of the World, a six minute, furiously edited, black-and-white masterpiece, was considered by many festival goers and critics to have been not only the best short to play at that year's festival, but to have been the best film of any length to play during the entire festival run. Since the release of The Heart of the World, he has continued to work steadily, completing several short films, as well as a pair of feature films, one of which is to be released later this year. Co-written by Maddin's long-time writing partner, George Toles, as well as Kazuo Ishiguro, Booker Prize winning author of The Remains of the Day, The Saddest Music in the World (2003), may well turn out to be the film that shows the world what many Manitobans and Canadians, as well as several cinephiles and professional film critics from around the world, have already known for years: that Guy Maddin is one of the most original, important filmmakers working today, regardless of geography or genre.

Born in 1956, Maddin seemed destined to live a life that would breed uniqueness and eccentricity at every turn. His father was a prominent hockey coach, as well as the business manager of Canada's national team, while his mother ran a beauty salon named Lil's Beauty Shop. And so, Maddin would spend many of his childhood days at either the Winnipeg Arena, seeing some of hockey's all-time greats both in practice and behind-the-scenes, or else he could be found playing with his older brother and friends at his mother's beauty salon. Even the way that Maddin tells stories about himself and his family, from receiving a piggy-back ride from Bing Crosby, to getting a cold from a cousin that resulted in a neurological infection and the permanent, persistent sensation of feeling like he is constantly being touched by ghosts all over his body, to finding out that his father was blinded in one eye as a child, because his father's mother had attempted to hold her son against her breast, but had accidentally poked his eye out with the pin from an open broach, indicates that Maddin either possesses an especially keen eye for life's little oddities, or else he has genuinely experienced what many people would consider an existence filled with extreme unusualness.

When Maddin was still a young boy, his older brother committed suicide, and while he does not often talk about it, suicide has certainly become a prominent theme that runs throughout his body of work. For that matter, fathers with missing eyes also frequently appear as characters in Maddin's films, and so, no matter how fictional and exotic the director's landscapes may seem, they are often fused with pieces of his own autobiographical history.

After graduating with a degree in economics from the University of Winnipeg, Maddin worked as both a bank teller, as well as a house painter, while meeting people whose friendships would serve him well, especially in terms of being able to eventually get his first films made and distributed. As fellow Winnipeg filmmaker, John Paizs, tells it, Maddin and himself would spend entire weekends at the house of fellow friend Steve Snyder, before any sort of formal film school existed in Winnipeg, and would watch hours upon hours of films on videotape and 16mm projection. Eventually, Paizs would go on to make several excellent short and feature films of his own (Springtime in Greenland [1981], Crimewave [1985]), while Snyder would go on to teach film studies as a professor in what would eventually become the University of Manitoba's film studies department.

***

With the release of Careful (1992), Maddin managed to impressively release his third feature in just six years. Careful is the story of an alpine village called Tolzbad, in which the villagers must forever speak quietly, out of fear that a loud voice might cause an avalanche and crush the entire village. In the film, several dominant themes that were already so much a part of Maddin's earlier work, continue to emerge. The obvious theme of an unsettled paternal relationship between fathers and sons is a dominant theme yet again, as is the presence of a one-eyed father figure. Of course, a one-eyed man could be considered to be as much an element of Maddin's own autobiography as it is a metaphor for a moviemaker himself. A film director is constantly looking through his lens, in an attempt to see the world in the same way that a camera sees the world and projector presents a finished film to the world: two-dimensionally. As well, the theme of a split existing between masculine and feminine, to the point of males and females being outright terrified of one another, also makes its way into the plot of Careful, and one cannot help but wonder how the masculine/feminine split, so present in Maddin's upbringing, would affect his eventual work. Having a father who coaches a hockey team, constantly surrounded by manly men doing manly things while at the arena, is about as masculine a scenario as one could expect to find oneself in. The contrast of having a mother who runs a beauty salon, and being surrounded by hair products and women having their hair, nails, and faces done up to look as womanly as possible, could only have creating a sexual counterpoint, which emphasized the contrast between the hyper-male and hyper-female worlds that Maddin grew up in.

In terms of locating the emotional content within Maddin's films, an impatient viewer may be inclined to conclude that these works are frequently devoid of emotion, or at least, that any genuine emotional content is hidden so deep beneath elements of irony, pastiche, visual style, and eccentricity, that a viewer may be wasting their time in attempting to locate emotion at all. However, while the link may not seem immediately obvious, I would be inclined to argue that Maddin's work shares a great deal with Wes Anderson's The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), especially in terms of locating emotion within each director's primary characters. Like The Royal Tenenbaums, Careful begins with an extended prologue, in order to set the tone of the story, as well as to explain who is who within the ensemble cast of players. As well, both films embrace the use of hyper-stylized settings and costumes, which critics of both films have criticized as being an exploitive device, designed to conceal the potential emotional content of each film. However, if a viewer is willing to show some patience with both the work of Maddin, as well as with Anderson's latest work, then they will eventually be rewarded with not only a subtle release of emotion by character, but they will also be exposed to a rarity in many contemporary films: an exploration of how emotions become so often improperly expressed, or outright blocked, whenever human situations become seemingly too complicated to handle.

While both Archangel and Careful would play at a number of prominent film festivals and win several major critical awards, culminating with Maddin becoming the youngest recipient ever of the Telluride Film Festival's Lifetime Achievement Award in 1995, the director has maintained that his biggest honour to date has been Careful's screening in Paris as part of the hundredth anniversary celebration of the birth of cinema, which also took place in 1995. And while Maddin seemed to be on a roll in the mid-'90s, especially after the release of Careful, the remainder of the decade proved to be a frustrating creative period for the director, to the point that he was ready to quit filmmaking at several different points, and could just not seem to get the kind of films he wanted to make off of the ground.

Maddin and Toles completed a script titled The Dikemaster's Daughter, which was to be set in nineteenth century Holland, or a fictitious Winnipeg, depending on which source material you read. The story revolves around a community comprising of dike builders, who must co-exist with the members of an opera company. The Dikemaster's Daughter was to be Maddin's follow-up to Careful, and would have been his fourth feature film, overall. At any rate, the project was in pre-production when one of the film's major sources of funding decided that they did not want to be a part of the film, and pulled out of the project, taking nearly half of the budget with them. As a result, Maddin was left empty handed, with no prospects on the horizons. It wouldn't be until nearly five years later, in 1997, that he would complete another feature film, despite having continued to refine his filmmaking skills by making a number of short films in the five year hiatus.

Twilight of the Ice Nymphs (1997) was to be Maddin's triumphant return to feature filmmaking. The script was ready, he had a cast of actors more well-known than any actors he had worked with before (Shelley Duvall, of Kubrick's The Shining (1980) and Altman's Popeye (1980), as well as Frank Gorshin, of camp fame from playing The Riddler on the 1960s Batman television series), and all with a larger budget than he had ever known before. The plot revolves again around a love story, and a man returning home to a land where the sun never stops shining, and yet, while the film contains several elements that are pure Maddin, it just cannot sustain itself for its 90 minute length. In many ways, the film feels compromised, an indication that Maddin's fervent imagination and creative independence were not a match made in heaven to distributors handing over a great deal of money to him, with the expectation that at least a semi-marketable movie would result. Through compromise, neither party ended up being satisfied, and the resulting work was Maddin's least satisfying feature film to date.

Of note, one of the most positive elements of Twilight of the Ice Nymphs is the picture's use of colour, a sort of photocopied pastel look that is no doubt an influence of having grown up in a beauty salon. One cannot help but be reminded of the gawdy surroundings that make up the typical salon, especially from the 1950s and 1960s, when Maddin would have grown up. If Maddin's father's poked out eye provided the lifelong metaphor of a filmmaker constantly seeing the world through one eye, then his mother surely provided her son with a taste what goes on in the preparation for making a film, with little Guy Maddin constantly seeing women in costume, being made up for the world to see.

Another positive element that emerged from the making of Twilight of the Ice Nymphs, is that it was at this point in Maddin's career that he began embracing the new generation of filmmakers emerging in Manitoba, in the hopes of assuring that the prairie province's legacy as a fertile moviemaker breeding ground would continue on for years to come. A young Manitoba filmmaker named Noam Gonick, who would eventually go on to write and direct the cult hit, Hey, Happy! (2001), was allowed onto the set of Twilight of the Ice Nymphs, as well as into Maddin's personal life. The resulting documentary, titled Guy Maddin: Waiting for Twilight, provides an almost uncomfortable view inside the process of a filmmaker who knows that his film is doomed to fail, even as he is still shooting it. At one point in the film, Maddin is so discouraged, that he even states, “This is my last film, ever.”

Thankfully, Maddin did manage to emerge from the pits of the Twilight experience. While he ended up taking a few years off to teach filmmaking at The University of Manitoba, all the while pondering whether or not he was actually finished with filmmaking for good, he would eventually be inspired and reinvigorated by the work of a young, talented filmmaker named deco dawson, who happened to take Maddin's filmmaking class, without ever having made a film before, and impressed Maddin so much with his first-time efforts, that he actually struck up a friendship with him outside of class. Dawson, only in his early twenties, would become obsessed with Maddin's filmmaking style, making films of his own that were at once homages to what Maddin had already accomplished, while being totally original, black-and-white, 8mm works that stood up completely on their own. In the years since having taken the filmmaking class with Maddin, dawson has gone on to become a sort of filmmaking partner/pupil to Maddin, having co-edited The Heart of the World, while aiding in the shooting and editing of Dracula: Pages from a Virgin's Diary (2001), Maddin's first feature film since Twilight of the Ice Nymphs.

With Maddin back on track with The Heart of the World, Dracula: Pages from a Virgin's Diary was his official return to feature filmmaking. The Bram Stoker character, which has been used on film to the point of overuse, was given new life, as the director recruited the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, in order to tell the story of Dracula in the way that he imagined it should be told. In the film, various grainy types of film are frequently mixed together with beautiful, sparse lighting, creating extraordinary results. If Dracula verifies anything about the Maddin aesthetic, it is that he is especially fond of taking something that he loves, whether it be a story that has been told so many times before, as is the case with Dracula, or even an actor that he loved as a child, such as Frank Gorshin, and then repackaging it completely, in order to point out the decay that naturally takes place to everything, over time. That Gorshin was once a young star, but is much older and forgotten now, or that Maddin continues to employ intentional splices and audio crackles into his films, as if they belong side by side with the decaying prints of original prints from the 1920s, indicates that he is as interested in how we can learn to love how things and people fade, as much as we love the things and people themselves.

Up to this point, most pieces written on Maddin seem to have built into them the subtext that while very few people have heard of him, more people need to hear about him. Indeed, after several failed attempts at making the feature film that will catapult him, if not to stardom, then at least to the next level of success in the world of experimental and independent film, The Saddest Music in the World may finally be the film to do it. Maddin's casting of this film is more accessible than ever before (Isabella Rossellini and Mark McKinney, of Kids in the Hall fame, star), as is, perhaps, the plot. The film surrounds a competition in which all of the countries of the world have a musical competition, in order to determine which country's music is the saddest, and therefore, which country has the right to claim the saddest history of any nation. With his latest film, Maddin will most certainly continue to explore his interest in music and sound, which has always been present in the ambient sound mix on the soundtrack to his films, as well as within the narratives of several of his works, most obviously Careful, with the townspeople that must barely make a sound when they speak, so as not to cause an avalanche, as well as the never realized The Dikemaster's Daughter, which would have involved a major subplot involving the members of an opera company.

Coming off the back-to-back-to-back success of The Heart of the World, Dracula: Pages from a Virgin's Diary, as well as Cowards Bend The Knee (2003), a film/art instillation that has played to rave reviews around the world, Maddin's yet to be released latest project promises to at least satisfy existing fans of his work, while recruiting some new fans along the way. Most importantly of all, The Saddest Music in the World promises to demonstrate a filmmaker working at his peak, and will hopefully continue to push the borders of a genre that Maddin invented himself, a genre that is at once beyond definition, and yet all too familiar to those already familiar with the director's past works.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home